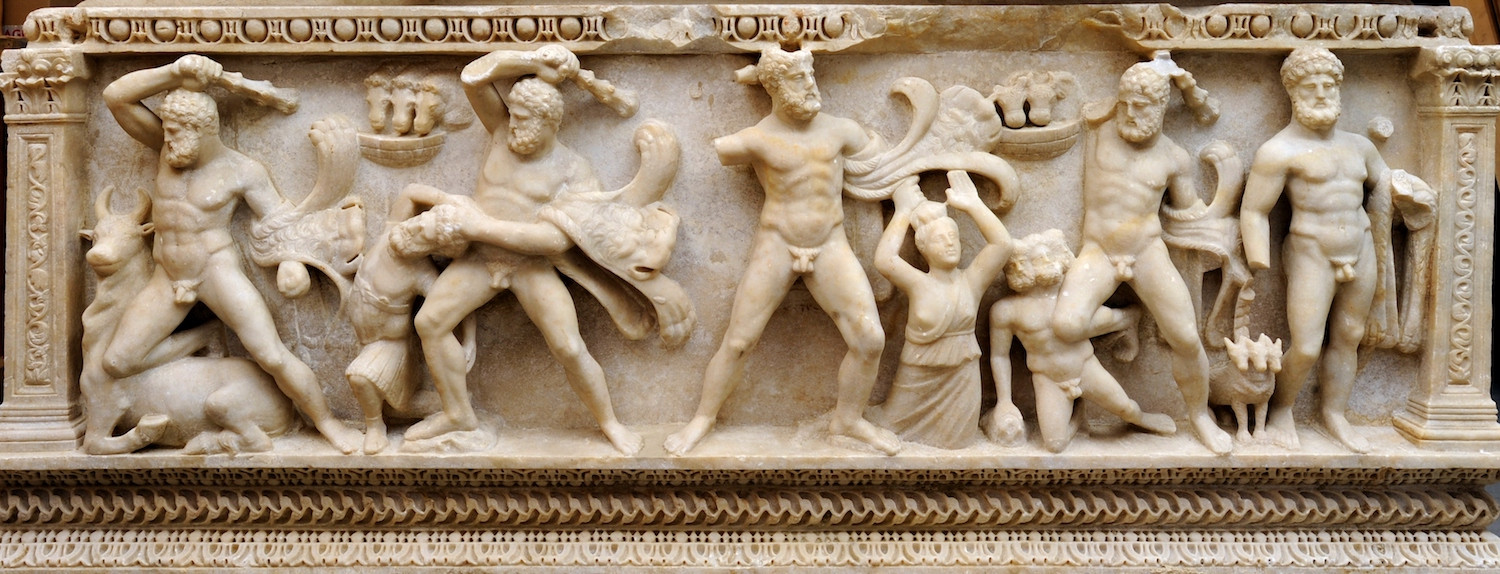

In September 2017, a long-awaited guest was greeted enthusiastically at the Antalya archaeological museum and was installed in a carefully-prepared pride of place. To be sure, this occasion was not so much the visit of a guest as the homecoming of a kidnapped native son. According to experts, the museum’s “Sarcophagus of Hercules” is the best-preserved of only four examples of such ancient stone coffins that are known to have survived. It arrived at the museum from its captivity in Switzerland.

Many of the details of the story of the restitution of this ancient Roman-period antiquity, which depicts the twelve labours of Hercules and was almost certainly carved in the 2nd century, would put a cloak-and-dagger thriller to shame. An affair involving an antiques dealer as well as two countries’ prosecutors, lawyers, archaeologists, and police and customs officials shows how much combatting the illicit trafficking in cultural heritage depends not just on the efforts of the country of origin but also on the enlightened attitudes and behaviour of other nations.

Geneva calling Ankara: “We’ve got something we think belongs to you”

Freeze-frame and cut to 2011: A Swiss government official contacts Turkey’s culture and tourism ministry and lets it be known that a magnificent and extremely well-preserved Roman-period marble sarcophagus that very likely was stolen from Turkey has turned up in a customs warehouse in Geneva. Turkish authorities are invited to collaborate with their Swiss counterparts in the effort to investigate the matter and return the artefact to Turkey.

The media soon get wind of the affair but the matter is reported along with speculation and ‘details’ by people who are completely in the dark about the real story. According to some, a Geneva freeport customs officer who was an archaeology buff saw a sarcophagus on TV very like the same one and tipped off the authorities; according to others, a young man happened upon the object completely by chance as he strolled around the warehouse. While it’s true that Switzerland’s freeport system potentially makes the country a haven for the international trade in art and antiques, it’s also highly unlikely that the Hercules sarcophagus’s re-emergence could have been the outcome of either scenario. There had to be something else to the story.

A sale gets cancelled

And indeed there was. When the Hercules sarcophagus first arrived at the Geneva freeport customs office, it was registered in the name of ‘Phoenix Ancient Art’ (PAA), a Geneva-based antiquities dealer owned by the Aboutaams, a family of Lebanese origin. It was stored in a warehouse belonging to Inanna Art Services (IAS), an international warehouse and freight forwarder[1].

In the spring of 2010, PAA was discussing the sale of the sarcophagus to the Gandur Foundation. Jean Claude Gandur, a Swiss billionaire and a serious connoisseur and collector of antiquities who intended to donate the sarcophagus to Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, an art and history museum in Geneva of which he was a major benefactor. Gandur had Marc-André Haldimann (the head of the museum’s archaeology section) and Jean-Yves Marin (the museum’s director) go to the Geneva freeport to examine the sarcophagus[2]. The pair soon realized however that the work’s documentation was not all that it ought to be. In fact, about the only documentation that did exist were statements claiming that the extraordinary object had been in the Aboutaam family’s collection since 2002. Owing to suspicions that the Hercules sarcophagus had been removed illegally from its place of origin, the sale to the Gandur Foundation fell through.

An inventory check turns up something under a blanket

In December of the same year, Swiss Federal Customs Administration authorities asked to examine PAA’s inventory. The Hercules sarcophagus was found in an IAS warehouse with a blanket draped over it.

Even more troubling were the questions raised about the work’s background: Who had owned the sarcophagus before PAA? Why had nothing about such an exceptional artefact ever been published before? Taking everything into account, Swiss authorities ordered that the sarcophagus be impounded while they conducted an investigation.

The examination of PAA’s inventory and the artefact’s discovery in IAS’s warehouse were no chance events. Switzerland’s freeport system had become indispensable to the operations of international art, antiques, and antiquities dealers but it was also appreciated that the system provided many opportunities for abuse, including illicit trafficking in cultural properties. To deal with this problem, the Cultural Property Transfer Act was passed in 2005. This law effectively incorporated the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transport of Ownership of Cultural Property into Swiss federal law[3]. Among other things, the act requires art dealers to prove that items in their inventories arrived there legally. So the discovery of the PAA-owned Hercules sarcophagus in the IAS warehouse was no fortunate fluke: it was the beneficial outcome of Switzerland’s efforts to protect the world’s cultural heritage.

A six-year struggle begins

When Turkish authorities were alerted to the investigation launched by the Geneva public prosecutor, another was initiated by his counterpart in Antalya. In 2011 the Swiss Federal Office of Culture announced that the sarcophagus’s marble was originally from the ancient Dokimeion quarries, which are located today in Afyon province’s İscehisar township. It turned out that this particular one was from an illegal dig that took place at the site of ancient Perge in Antalya during the 1960s but its whereabouts before it came into PAA’s possession are still unknown.

“Unquestionably smuggled out of Turkey”

The investigation did not end there of course. Swiss and Turkish prosecutors’ offices worked together to discover as much as they could about the sarcophagus’s origins and history. In 2013, a public prosecutor from Geneva by the name of Claudio Mascotto arrived in Turkey and, accompanied by his Turkish colleagues, visited the site of ancient Perge to see things for himself. Mascotto also met with someone who was then serving time on a different smuggling charge and who confirmed that the artefact had been illegally excavated and taken out of Turkey.

Investigators also consulted the expert opinions of archaeologists. Professor Haluk Abbasoğlu and Professor İnci Delemen, both of whom were familiar with the region, confirmed that such a sarcophagus could only have been the product of an illegal dig.

Professor Marc Waelkens, who was head of the excavations at the site of ancient Sagalassos in Antalya’s Ağlasun township at the time of these investigations, submitted a 70-page report[4] in which he concluded that stylistically the sarcophagus conformed to a type, was a Dokimeion-marble sarcophagus of western Asia Minor origin from Perge. Nearly all the testimony of witnesses and experts and the findings of reports pointed to one inescapable conclusion: the Hercules sarcophagus had been stolen from Perge.

PAA’s efforts come to nought

On 21 September 2015, Swiss authorities finally ordered that the Hercules sarcophagus be returned to Turkey. No penalties were imposed on PAA however for having brought the artefact into Switzerland. PAA’s owners, the Ali and Hicham Aboutaam brothers, maintained that the sarcophagus had been purchased legally by their father (and company founder) Sleiman Aboutaam in the 1990s in accordance with rules that were in effect at the time. Sleiman Aboutaam himself died in an airplane accident in 1998 and the artefact was part of his sons’ inheritance. Exactly how the sarcophagus was dug up and how it came into the Aboutaam family’s possession has never been made clear. Be that as it may, on 2 May 2016 the Geneva Court of Justice upheld the order repatriating the sarcophagus to Turkey. Just when it seemed that nothing stood in the way of this restitution, the Geneva court’s ruling was challenged by PAA in the Swiss Federal Court. Hoping to prevent any further delay in the proceedings, Turkish authorities themselves intervened. Eventually PAA withdrew its objection and its appeal was quashed. With nothing left to frustrate the restitution, the Hercules sarcophagus finally returned to Turkey on 14 September 2017.

The repatriation of the Perge Hercules Sarcophagus is a cultural heritage preservation story no less remarkable than the Twelve Labours of Hercules that it depicts. Turkey’s exemplary involvement and efforts leading to the restitution should be an encouragement to every other country whose cultural properties have been ransacked. The story is equally remarkable because it shows what can be achieved if countries act responsibly when they discover stolen objects in their midst. As this example makes it clear, combatting illicit trafficking in cultural properties is possible nowadays only through international efforts and cooperation.

Sources:

[1] “Un sarcophage romain saisi aux Ports francs de Genève”, RTS Info https://www.rts.ch/info/regions/geneve/3865869-un-sarcophage-romain-saisi-aux-ports-francs-de-geneve.html

[2] “Repatriation: Roman sarcophagus held at Swiss Freeport finally clears last hurdle for its return to Turkey”, ARCA http://art-crime.blogspot.com/search?updated-max=2017-03-25T22:38:00%2B01:00&max-results=10&reverse-paginate=true&start=16&by-date=false

[3] “Federal Act on the International Transfer of Cultural Property”, UNESCO http://www.unesco.org/culture/natlaws/media/pdf/switzerland/ch_actintaltrsfertcultproties2005_engtno.pdf

[4] “Marc Waelkens tarafından hazırlanan rapor Herakles Lahdi’nin Perge kökenli olduğunu gösteriyor”, Aktüel Arkeoloji www.aktuelarkeoloji.com.tr/marc-waelkens-tarafindan-hazirlanan-rapor-herakles-lahdinin-perge-kokenli-oldugunu-gosteriyor-0

* Cover photo: Public Ministry of Geneva